Why LLM API Calls Break in Production

When you build an integration with an LLM provider and test it locally, everything usually looks fine. You send a request, you get a response, and you move on. The problems start when you deploy the same code to a cloud environment. You begin to see errors such as “connection reset by peer”, timeouts, or calls that appear to hang for a long time and then fail. The failures are intermittent and hard to reproduce. Most of the time your logs do not tell you much either.

Nothing in your application code has changed and the LLM provider is the same. The difference is the infrastructure between your service and the provider.

In this series of posts we will look at that infrastructure in more detail. We will focus on why LLM calls behave differently from typical REST requests, how cloud networking interacts with them, and what configurations you need to make these calls reliable.

This first post is about understanding the “why”. We will walk through a typical LLM request from your backend to the provider and highlight the weak spots that only show up in production.

The Hidden Complexity of an LLM API Call

It is common to think of an LLM request as a single HTTP call that either succeeds or fails. In reality, the call crosses several layers of networking infrastructure. Each of these layers has its own timeouts, limits, and ideas of what a “healthy” connection looks like.

On your laptop almost none of this matters while in a cloud environment it often becomes the main source of problems.

A Typical Request Path (and Where It Can Break)

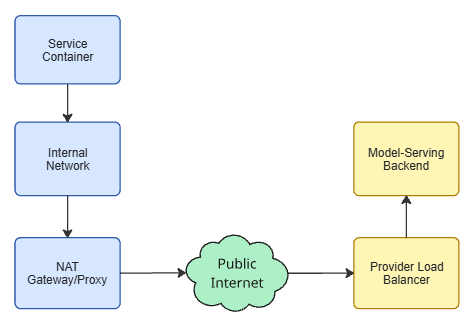

A request from your backend to an LLM provider usually goes through the following steps:

- Your service container The HTTP client opens a TCP connection or reuses one from a connection pool.

- The internal network The request moves through your VPC or container network. This adds hops and some latency but is rarely the main issue.

- A NAT gateway or outbound proxy This allows your private services to talk to the public internet. It often enforces idle timeouts on connections that do not carry data for a while.

- The public internet Packets traverse routers and links you do not control. Latency, jitter, and occasional packet loss are normal here.

- The LLM provider’s edge A load balancer terminates the connection and forwards it to a backend service.

- The model-serving backend The provider processes your request, possibly queues it, and then generates and streams the response.

Each of these components can drop a connection or decide it has been idle “too long”. Normal API calls that complete in a few hundred milliseconds do not usually trigger these limits. LLM calls that run for tens of seconds or longer do.

By the time you see “connection reset by peer” in your logs, the decision to close the connection has been made somewhere along this path, often outside your application and without a clear signal at the HTTP level.

Why LLM Calls Stress the System More Than Normal APIs

Three properties of LLM traffic make these issues much more likely.

1. Long response times

Many web APIs are designed around sub-second latencies. LLM calls often take 10–60 seconds, and some workloads take several minutes. Infrastructure that was tuned for short-lived requests tends to treat these long-running connections as abnormal.

2. Streaming behaviour

LLM providers frequently stream responses as a series of small chunks, using mechanisms such as server-sent events or chunked transfer encoding. Between chunks there can be noticeable idle periods where no data flows.

For components like NAT gateways or proxies, this can look like a forgotten connection. If the idle period exceeds the configured timeout, they may drop the connection even though the LLM backend is still working on your request.

3. High variability

Latency for the same endpoint can vary widely. It depends on the prompt size, the model, queueing on the provider side, and current load. Two similar requests might complete in very different times.

This variability makes it difficult to pick “safe” timeouts based on intuition. Values that seem conservative in testing can still be too aggressive under real production traffic.

On a local machine, you often have a direct path from your process to the provider with no NAT, minimal connection pooling, and very few long-lived idle sockets. In production you have all of those, and LLM calls exercise them heavily. That gap explains why everything appears stable in development and then starts to fail once you deploy.

The Cloud Layer and Idle Connections

Once you move your LLM integration to a cloud environment, there is usually one more piece between your service and the public internet. Your requests no longer go straight from the container to the LLM provider. They pass through an extra hop that manages outbound traffic for many services at once.

That extra hop is often a NAT gateway or an outbound proxy.

A NAT gateway (Network Address Translation gateway) lets many internal services share a small number of public IP addresses. From the outside world, all your services seem to be talking from the same few IPs.

An outbound proxy is a service that forwards HTTP(S) requests on behalf of your application. It can enforce policies, log traffic, and apply security rules.

Both components have to track a large number of open connections and clean them up when they appear idle or abandoned. This is where long-lived LLM calls start to conflict with cloud defaults.

How NAT Gateways Treat Idle Connections

A NAT gateway keeps a table of active connections. For each one it stores:

- internal source IP and port

- external destination IP and port

- the time it last saw traffic on that connection.

To avoid running out of memory or ports, it periodically scans this table and removes entries that have not seen any traffic for a while. The exact thresholds differ by provider, but idle timeouts of roughly 30–90 seconds for TCP connections are common.

A few points are worth noting:

- The NAT cares only about packets, not about your application logic. If no packets pass for longer than the configured timeout, the connection is treated as idle.

- When the NAT removes an entry, it does not notify your application. It simply deletes the mapping and forgets about it.

From the NAT’s perspective this is just housekeeping. From your application’s perspective there is still a live TCP socket object, but the path through the network has been broken in the middle.

Outbound proxies behave similarly. They maintain internal state about open connections and apply their own idle timeouts. The effect is the same: long-lived or intermittently active connections are more likely to be dropped.

What This Does to Your LLM Connections

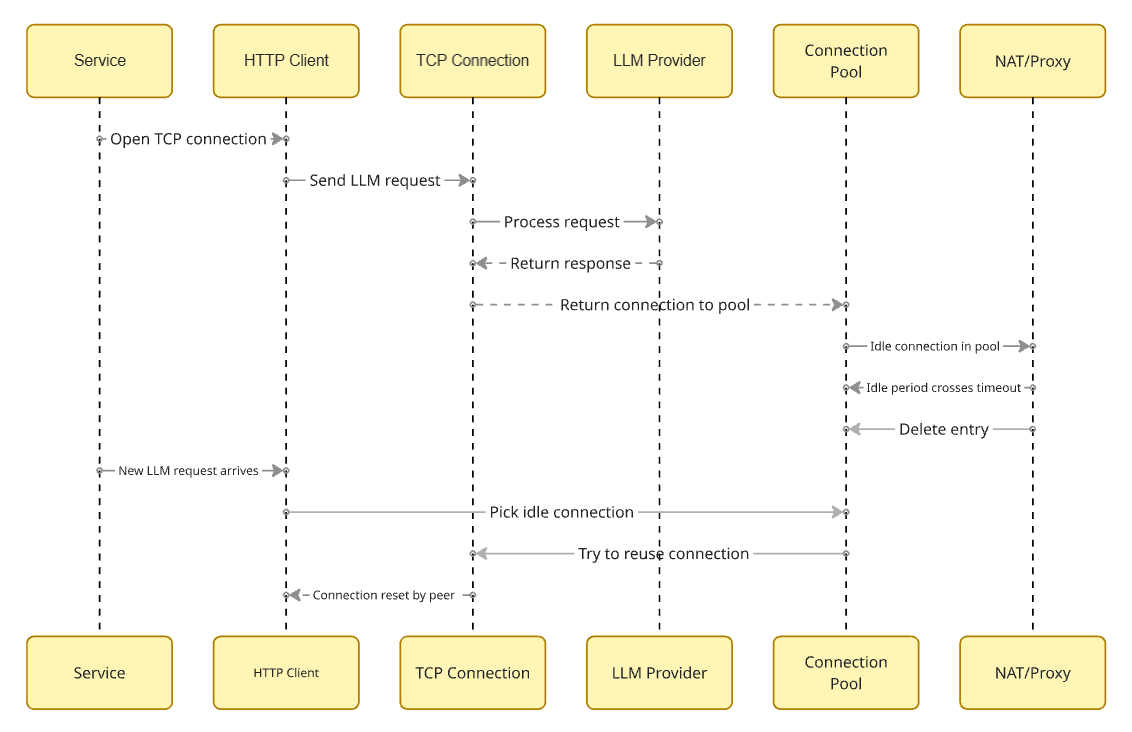

Combine this behaviour with an HTTP client that reuses connections from a pool and you get a characteristic pattern:

- Your service opens a TCP connection to the LLM provider and sends a request.

- The request completes. The HTTP client returns the connection to its pool.

- The service does not send any more LLM requests for some time. The connection remains idle in the pool.

- The idle period crosses the NAT or proxy timeout. The intermediate component deletes its entry.

- A new LLM request arrives. The HTTP client picks the “idle” connection from the pool and tries to reuse it.

- Somewhere along the path, the packets no longer match any known connection. The client sees connection reset by peer, broken pipe, or a similar low-level error.

From the application’s point of view this looks like a random network glitch. The socket object was valid, DNS resolution succeeded, the provider endpoint was configured correctly, the only piece that changed state was the cloud networking layer in the middle, and it did so without exposing any clear signal to your code.

You usually do not see an HTTP error code in this situation. The failure happens below HTTP, at the TCP level, so all you get is an I/O exception.

Why This Is Easy to Miss

This kind of failure is often misdiagnosed for a few reasons:

- It appears more often under low or bursty traffic, when connections have time to sit idle, than under steady high load.

- It tends to affect the first request after a quiet period. That pattern is rarely tested explicitly.

- Each participant sees only part of the story: Service logs show a transport-level error. The LLM provider may see a client that disconnected suddenly. The NAT gateway or proxy usually has no application-level logging you can access.

Because of this, teams sometimes blame the provider (“they are dropping connections”) or the HTTP client (“the library is unreliable”), when the real problem is the interaction between connection pooling and idle timeouts in the cloud layer.

Later in this series we’ll look at how to configure your HTTP client so that it does not try to reuse connections longer than the infrastructure can support. That is where connection pool tuning and eviction settings come in.

Why It Works Locally but Fails in Production

At this point the behaviour is clear: long-lived or idle connections do not play well with cloud networking defaults and connection pooling.

It still leaves a practical question: why do you almost never see this when developing locally, and why does it show up so quickly after deployment?

The short answer is that your local environment and your production environment behave very differently, even when they run the same code.

What Happens in Local Development

On a typical developer machine, the setup looks roughly like this:

- Your application runs on your laptop.

- It opens a TCP connection directly to the LLM provider over the public internet.

- There is usually no NAT gateway in front of you that enforces short idle timeouts.

- You send a few requests in a row while you are testing a feature.

In that situation:

- Connections are often created and torn down quickly.

- There is little or no connection reuse from a pool.

- Idle periods are short, because you are actively exercising the feature.

- If something fails, you try again immediately and do not stare at idle services for minutes.

You are also not simulating real traffic patterns. You are not leaving the application idle for ten minutes and then sending one request. You are not running ten containers that all share the same NAT gateway. You are not doing rolling deploys while long-lived connections are open.

Under these conditions, most infrastructure defaults are “good enough”, so development appears smooth.

What Changes in Production

In production, the same code runs in a different context:

- Your service usually runs in containers or VMs inside a VPC.

- Outbound traffic goes through a NAT gateway or an outbound proxy with its own timeouts.

- The HTTP client uses connection pooling to avoid the cost of creating a new TCP connection for every request.

- Real users generate traffic with gaps, bursts, and periods of low activity.

Some concrete differences that matter:

- More reuse of connections The client keeps TCP connections open for longer and reuses them across many requests. This increases the chance that a connection will sit idle just long enough to hit a NAT timeout.

- More idle time Real traffic is uneven. You might have a few minutes of silence, then a handful of LLM calls, then another quiet period. These gaps are exactly when idle connections get cleaned up.

- More concurrent containers Multiple instances of your service may share the same NAT gateway. The gateway has to be more aggressive in pruning idle connections to stay within its limits.

- Infrastructure updates Rolling deployments, autoscaling, and restarts happen while some connections are open. Any of these can interact poorly with long-running LLM calls.

From your application logs alone, it is easy to miss these changes. All you see is that requests which behaved correctly in development now fail intermittently in production with low-level connection errors.

The “First Request After Idle” Pattern

One specific pattern is worth calling out because it is common and rarely tested.

- The service is quiet for a few minutes.

- During that time, open connections in the pool cross the idle timeout at the NAT or proxy and are removed there.

- The next user triggers an LLM request.

- The client reuses one of those “idle” connections.

- The request fails immediately with a transport error.

Once there is steady traffic again, the pool fills with fresh connections, and errors disappear. If you only look at high-traffic periods, the system appears stable.

This is why you may see error reports from users who “just tried it after a while” while your own load tests, which hammer the service continuously, show no issues.

Understanding this difference between local and production behaviour is important before touching configuration. Otherwise it is tempting to make random tweaks to timeouts or retries without addressing the root cause: how long connections live and how they are reused in the presence of cloud networking timeouts.

The next step is to look at the concrete symptoms this produces in logs and monitoring, and to separate them from other classes of failures.

The Symptoms You See (and Sometimes Misdiagnose)

By now we know what is happening on the network path. The next question is how it shows up in your day-to-day work. In practice, you do not see “NAT idle timeout exceeded” in your logs. You see a mix of errors that look random and are easy to misinterpret.

Most of them fall into three categories: transport errors, timeouts, and odd traffic patterns.

Transport Errors at the Worst Possible Moment

The most common signals look roughly like this:

- connection reset by peer

- broken pipe

- remote host terminated the handshake

- PrematureCloseException or similar from your HTTP client

They often appear on the first LLM request after the service has been quiet for a few minutes, or on requests that otherwise look routine with no obvious correlation to provider incidents.

If you are using retries, these errors may also show up as “retryable noise” in your logs. You might see a small but steady background rate of transport-level failures that are “magically” fixed by a retry.

The important detail is that these errors are usually not tied to a specific prompt, model, or user action. They are tied rather to the state of the underlying connection.

Timeouts That Do Not Quite Make Sense

The next group of symptoms are timeouts that feel inconsistent:

- Some calls run for a long time and then fail with a client-side timeout, even though the provider is generally responsive.

- Other calls for similar inputs finish quickly.

- Increasing timeouts in the HTTP client helps a bit, but does not eliminate the problem.

In a pooled-connection setup, these timeouts can be a delayed effect of the same underlying issue. Your client sends a request on a stale connection, the first bytes never reach a valid peer, so the client waits until its own timeout expires.

Strange Traffic Patterns

There are also a few aggregate patterns that show up in metrics:

- Error spikes after periods of low traffic, while high-traffic periods look healthy.

- A small but persistent error rate that does not match provider status pages.

- Retries that succeed quickly most of the time, which makes the system “feel” fine despite the underlying instability.

If you only monitor success rates over longer windows, these problems can stay hidden. For example, a 1–2% transport error rate that is always fixed by a retry will not trigger many alerts, but it is a clear sign that connections are being dropped somewhere in the path.

Typical Misdiagnoses

Because the network path is not visible in logs, teams sometimes frame the problem in the wrong way:

- “The provider is flaky.”

- “The HTTP client has bugs.”

- “Something is wrong with TLS.”

- “We need more retries.”

All of these are possible, but if you see:

- transport errors around idle periods, and

- a strong “first request after idle” pattern,

then the more likely explanation is the interaction between cloud networking timeouts and your connection pooling strategy.

Before touching provider settings or switching libraries, it is worth confirming whether your client is reusing connections longer than your infrastructure can tolerate.

What This Means for Your Configuration

At this point we have most of the pieces needed to reason about our LLM failures:

- The request crosses several layers of infrastructure, not just our code and the provider.

- Cloud components such as NAT gateways and proxies aggressively clean up idle connections.

- Our HTTP client may be reusing those idle connections long after the cloud has silently dropped them.

- The result is a cluster of transport errors, especially after idle periods, that look random if you only watch your application layer.

Before touching any configuration, it is useful to reframe how you look at these problems. When you see intermittent connection reset by peer or similar exceptions, especially on the first request after a quiet period, treat them as a signal about connection lifetime and reuse, not just “bad luck on the network”.

A few practical questions you can ask yourself at this stage:

- Do errors correlate with low-traffic periods or deploys, rather than with specific prompts or models?

- Do retries usually succeed immediately, suggesting the problem is the state of the existing connection rather than the provider itself?

- Do you have any visibility into how long connections stay in your pool before being reused?

If the answer to these is “yes” or “I don’t know”, then you are in the territory this series is about.

In the next part, we will move from diagnosis to concrete changes. We will look at how to configure connection pools so that:

- idle connections are rotated before cloud timeouts hit,

- your pool size matches realistic LLM latencies,

- the “first request after idle” failure pattern is largely removed.

After that, we will add timeouts and retries on top of a pool that behaves correctly, rather than using them to paper over underlying connection issues.